| Question:

When I was travelling by air recently,

the glass fell off of my watch. Is this very common and why did it happen?

Jody Abrams, Devon, England

To have the glass fall

off of your watch is certainly annoying, although the reason for this fairly uncommon

event can be easily explained. Watches that are designed to be water-resistant prevent

water from entering the case. That is obvious. But, it also means that air cannot enter

the case either. In addition, the air that is already inside the case cannot get out.

Therefore, the pressure inside of a watch is the same as the ambient pressure at the

factory where it was assembled. And, because the watch is air-tight, this pressure will

not change.

If you are in an aeroplane flying at an altitude of 10,000 meters, you still have enough

oxygen to breathe because the cabin pressure is maintained artifci-ally using air

compressors. If the cabin loses this pressure, oxygen masks will drop from the overhead

compartments. However, the air pressure in a plane flying at this altitude is not the same

as it is on the ground. It would simply be too expensive to keep the cabin pressurized to

such an extent. In general, airlines maintain the pressure inside their aircraft

equivalent to that at the top of a 2,000 metre high mountain. As a result, when the

aeroplane begins its descent towards the airport, many change when the aeroplane took off

since its ascent was more gradual and their ears would have had more time to adjust to the

decreasing pressure.

Getting back to watches… Unless they were assembled at 2,000 meters of altitude,

water-resistant timepieces maintain the ground pressure. When they are taken in a craft

flying at 10,000 metres, their internal pressure will therefore be higher than that of the

cabin. From a theoretical point of view, they should have a tendency to explode. Of

course, we don’t find watches exploding in flight, although from time to time, we do

observe that the glass is ejected from the case thus allowing pressure equalization. If

this happens, it is probably due to a weakness in the construction. With modern watch

production, however, the glass should not fall out. Normally manufacturers test their

watches under conditions of reduced ambient pressure (such as in an aeroplane) as well as

under conditions of increased pressure (such as under water).

In your case, the manufacturer of your watch should be responsible for this imperfection

and should offer to repair the piece at no charge. In addition, even if there was only one

such problem with his products, a conscientious manufacturer should review the manner in

which all glasses are mounted in their cases.

Question:

What does the expression

“guilloché” mean?

Alfred Lo, Brisbane, Australia

The term

'guilloché' is a French term that means 'engine-turned'. However these days, the French

word is often used in English when dealing with the subject of watchmaking. It is used to

describe a technique for engraving a particular type of ornamental motif on an object.

Generally, this design consists of wavy and interlacing lines that cross at regular

intervals.

This shimmering pattern is created using a machine called a 'tour à guilloché', or

'rose-engine' in English. This apparatus is particularly ingenious and can combine several

types of movements to obtain varied decorative patterns. We can get a myriad of designs by

using different combinations of cams mounted on the axis of the rose-engine. The fixed

feeler-spindles push on the various cams, causing the lathe mounted in the cradle to

oscillate laterally while turning in front of the stationary engraving tool mounted on the

other side of the device.

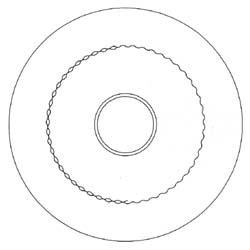

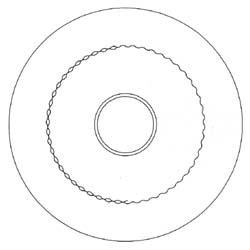

The most classical form of the guilloché motif is the 'barley-corn' pattern. It is shown

in Figures 1a and 1b.

|

|

| Figure 1a: The first machining stage and the

beginning of the second stage for the barley-corn pattern using the guilloché technique.

In reality, the machining starts at the edge of the inner central zone to be left blank

then moves outward. |

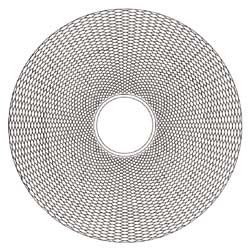

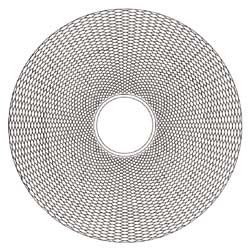

Figure 1b: The finished barley-corn pattern

using the guilloché method. The inner central zone has been left blank. |

This design can be off-centred to leave a space for the addition of a

monogram, logo or brand name (see Figure 2). Abraham-Louis Breguet often used dials that

had been finely decorated with the barley-corn pattern in his watches.

|

|

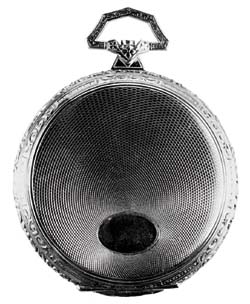

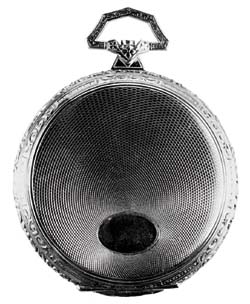

| Figure 2: The back case of a pocket watch

that has been decorated with an off-centred oval guilloché technique leaving a blank

elliptical area near the base. |

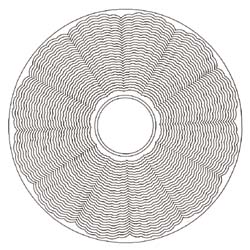

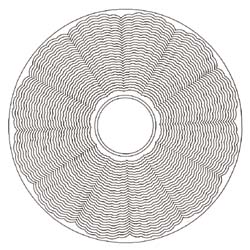

Figure 3: An example of the 'flinqué'

pattern, or a design composed of radiating scallops made by an engine-turning or

guilloché technique. |

In general, however, most dials were decorated with a pattern consisting of

radiating scallops or festoons with twelve spokes. This type of guilloché design is

called 'flinqué' in French but is now also used in English. Figure 3 illustrates a good

example of this type of engraving. The engine-turning technique can also be used to obtain

straight lines as well as to create inter-esting geometric decorations, as shown in Figure

4.

This technique may also be used to approximate classical engraving, for example, to make

arrangements of leaves or flowers, complicated geometric designs and even portraits.

Figure 5 shows an excellent example of a highly detailed and intricate guilloché piece of

art. This plaque contains elaborate ornamentation and portraits that were made around 1850

by Alcide Nicolet, a craftsman known for the high quality of his very special work.

|

|

| Figure 4: The guilloché method can also be

used to obtain straight lines and geometrical patterns as seen on the case of this pocket

watch. |

Figure 5: This plaque was created around

1850 by Alcide Nicolet, and shows the many intricate and detailed possibilities for the

engine-turning or guilloché technique. |

Already in 1819, rose-engine machines were operating in La Chaux-de-Fonds. A letter

written by Auguste Courvoisier to his brother Frédéric describes a reception given for

the Royal Prince of Prussia when he visited the small town: ‘The Royal Prince was

presented with a gold medallion. On one side was a portrait of the King that had been made

by Henri Banguerel using the same guilloché technique that was used in decorating small

boxes. The Prince seemed very satisfied, as much as with his gift as with the battalion

and the repast that was prepared in his honour at the town’s offices.’ I might

add in the interest of historical detail, that, ironically, the recipient of this letter

was none other than the future leader of the rebellion that provoked the separation of the

Neuchâtel region from the Prussian empire.

The guilloché devices, which were the most highly perfected in their day, could also

mass-produce medallions in addition to making objects with very complicated relief

designs. The depth of penetration and motion of the engraving tool were guided by a

feeler-spindle attached to a hand-crafted model of the motif.

In the last century, these techniques were very highly appreciated and often used to

decorate timepieces. Today, how-ever, they have lost much of their lustre as the demand

for watches with smooth clean lines continues to grow. |

PRECISION WATCH REPAIR BY CHARLIE SQUIRES

PRECISION WATCH REPAIR BY CHARLIE SQUIRES